In my programming language, currently codenamed Brick, I want to allow developers to pull in platform-native libraries written in other languages. Brick compiles to WebAssembly (wasm), and wasm is totally sandboxed by design. Without functions provided by the environment (“imports” in wasm lingo), a wasm module can have no side effects when run. I want Brick programs to have plenty of side effects, like making web requests or drawing graphics to the screen.

[!info] What does a wasm import look like?

Let’s use Rust as an example. This is how we would define an external[1] function:

extern "C" { fn do_side_effect(arg1: i32, arg2: f32); }Here’s the corresponding wasm, expressed in the Web Assembly Text (WAT) format:

(import "env" "do_side_effect" (func $do_side_effect (param i32 f32)))

On desktop I’m running Brick programs via wasmtime, a wasm runtime maintained by the folks behind the wasm spec. It’s written in Rust and exposes a Rust API, which allows us to attach Rust functions as a wasm module’s imports. This is great, because it allows us to include external libraries like tokio for web requests or macroquad for graphics. The linking API looks like this:

linker.func_wrap(

"bindings", // the name of the WASM module being imported

"fill_rect", // the name of the import in that module

move |x: f32, y: f32, w: f32, h: f32| {

draw_rectangle(x, y, w, h, Color::WHITE);

},

)?;The only problem is that each of these bindings need to be written by hand in our Rust program. There’s no way to introduce new bindings at runtime, which makes it hard for Brick packages to use any external code I didn’t plan for.

Here’s the goal: link our wasm binary directly with a dynamic library, without needing to hand-write these bindings.

[!info] What is linking? Linking is the process by which different binary objects form one application on an operating system. There are two types of linking: dynamic and static. Dynamic linking means that our application knows what libraries it needs to run, and functions it needs from those libraries, but it doesn’t store those functions directly. Instead the program asks the operating system for the library each time it runs[2]. Static linking bundles a library’s contents directly into the binary, and is favored by Rust and Go. It allows the final result to be easily portable.

In this case, because I want to include unforeseen-at-compile-time code, I need to use dynamic linking.

High Crime: Break down the sandbox

Enter wasmtime-dl, a very bad idea I had. My goal was to break a hole in the side of the sandbox, and allow Brick packages to link to arbitrary dynamic libraries.

The first design I sketched out was simple: given a set of function definitions, link the dynamic library with wasmtime. I had no idea how to accomplish this, but I’m in batch at the Recurse Center! It was time to work at the edge of my abilities.

A long time ago, I wrote games in C. I remembered trying and failing to set up hot reloading for the games, so I could recompile them without having to relaunch the game. In those explorations I encountered the dlopen Linux system call, which allows you to load dynamic libraries at runtime. I searched “dlopen Rust”, which was a good-enough starting point. I found a few crates that all did roughly the same thing: open a dynamic library, and return a function pointer for a given symbol name in that library.

Of the available crates I settled on libloading; here’s an example of how it works from the docs:

unsafe {

let lib = libloading::Library::new("/path/to/liblibrary.so")?;

let func: libloading::Symbol<unsafe extern fn() -> u32> = lib.get(b"my_func")?;

Ok(func())

}So now we can definitely take a dynamic library and starting pulling functions out of it. Great, on to the next step: grabbing these functions dynamically.

High Crime: 1 million lines of Rust

Here I encountered my first major obstacle. I need to tell Rust what the type of the function pointer is before I can call it. I don’t think this is even a safety concern; how can the compiler emit code if it doesn’t know what values will be sent into the function call? Unfortunately I don’t know the type at compile time; I’ll be reading the types in at runtime.

I decided to solve my problem with a little code generation. By creating a very big match statement, I could dynamically pick the right type based on the runtime information. If the function definition was (f32, f64, i32, f32) then I would match that tuple, and that match branch would create a function pointer with type fn(f32, f64, i32, f32). Type problems solved! I wrote a quick Python program to generate my match statements and hit run.

After it ran for a few seconds I started to get suspicious. “Why is it taking so long?”, I thought. I had tried to generate up to 16 arguments (which seems like a reasonable number of arguments to me), with an optional return value. In wasm, types may be 32 or 64 bit and they may be integers or floats, giving us four types: i32, f32, i64, and f64. Surely the number of combinations couldn’t be that great! I punched it into Wolfram Alpha just to double check and almost fell out of my chair: 4 parameter types and one optional return type, for every parameter length up to 16, gives over one million combinations.

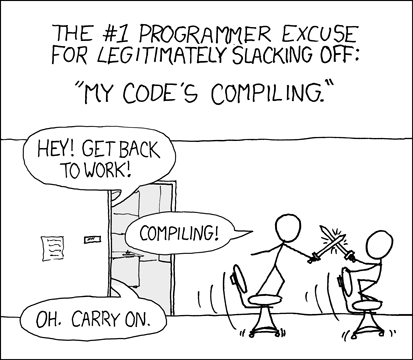

Numbers! How could you do this to me??? Let alone the time to generate 3 million lines of Rust, imagine the time to compile it. Forget office fencing, you’ll have time to run a whole office LARP!

I scoped my ambitions way down and generated up to 4 parameters instead, which is still a CPU-crushing 15,700 lines of Rust. Even though it took minutes to compile, I had my first working prototype.

The interface looked like this:

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

pub enum ValType {

I32,

F32,

I64,

F64,

}

pub struct WasmFuncImport<'a> {

pub module: &'a str,

pub name: &'a str,

pub params: &'a [ValType],

pub returns: Option<ValType>,

}

pub unsafe fn link(

// linker provided by wasmtime

linker: &mut Linker<()>,

// path to the dynamic library

dynamic_lib: impl AsRef<OsStr>,

// type definitions for the wasm imports

imports: &[WasmFuncImport<'_>],

) {

// ...

}The generated code in that function is sorta unreadable, but you can check it out on GitHub if you want to see it for yourself.

Misdemeanor: Why define the bindings?

You shouldn’t have to define the bindings - they’re right there in the binary! I’m not sure if I realized this in the shower, or on the train, or at the gym, but it hit me like a bolt of lightning. A wasm binary defines the types of its imports, including what parameters and return values functions have.

[!INFO] Remember our Rust example from before?

do_side_effect’s type is encoded right in the wasm:(import "env" "do_side_effect" (func $do_side_effect (param i32 f32)))

That means we can save some work for wasmtime-dl’s caller. Instead of asking them for some external definition for each function, we’ll just use the one provided by the wasm binary.

The first experimental version worked! Driving the function bindings by examining the imports of the module itself meant that the user only needed to provide a wasm module and a dynamic library, and wasmtime-dl could drive the rest. Our interface from before can remove user-provided binding definitions entirely; doesn’t it look so much simpler?

pub unsafe fn link(

// linker provided by wasmtime

linker: &mut Linker<()>,

// path to the dynamic library

dynamic_lib: impl AsRef<OsStr>,

// the wasm blob as loaded by wasmtime

wasm_module: &Module,

) {

// ...

}It was only after I had done the work that I realized it was fatally flawed. In wasm, pointers are represented as i32 values. The wasm binary format provides no distinction between a regular integer and one that is used as a pointer, but that distinction matters a lot to our binding program. Before we can pass the pointer to an external library, we need to add the offset where the wasm VM’s memory starts. Within wasm a pointer might look like the value 12 (the 12th byte of the VM’s memory), but outside it will look like more like 0x0ffac12 (the actual RAM location where the WASM VM’s memory is stored, plus 12).

We could just have annotations for which parameters and return values of imports functions are pointers, but what’s the point[3]? Once we need annotations on some functions, we may as well accept the need for annotations on every function. I added a new variant to ValType to represents a pointer; it counts as an i32 on the WASM side and a u64 on the host side.

Misdemeanor: Floats and ints… they’re all just bytes, right?

At this point I had another good? bad? idea. To cut down on the combinatorial explosion, what if I pretended that all float parameters are ints? An f32 or an i32 are both 32-bit chunks of data; the only difference between them is how you interpret those 32 bits. By treating all parameters to the dynamic library functions as i32 or i64 we can drastically cut down on the number of generated match cases.

This required some finagling. First, instead of getting to use the convenient type-safe methods on wasmtime’s Linker, I had to drop down into the less-convenient, less-safe, and slower “raw” binding mode. Second, I discovered that punning an f32 into an i32 was a little more complicated than I initially expected. After a few iterations where the bindings produced total gibberish, I ended up with a pretty simple use of the bytemuck crate to transmute the provided f32 bytes into an i32.

[!info] Binding Example

For a given function signature of

func(f32, i64), we can match it like this:( [ParamType::I32 | ParamType::F32, ParamType::I64 | ParamType::F64], None )

By constraining the combinatorial space, I managed to fit in up to eight parameters in the generated code. It still takes minutes to compile though, even on an M1 Mac, so it’s not exactly lightweight.

A snag: structs

I was excited to have created this horrible beast. To make a little demo I decided to pull in raylib, a simple C library for creating games, and call it from some wasm. As I scrolled through the raylib API, it hit me: wasm doesn’t know about structs! Any C function that takes a struct or union will expect it to conform to the C calling ABI; wasm only knows about its core primitive types. As it stands there’s no way to call a function that expects a non-primitive argument.

This problem isn’t technically insurmountable, but it feels that way in a practical sense. I’m sure I could add an elaborate layer to marshal wasm parameters into structs, but that would explode my combination issue even further. Instead I decided to declare victory (or defeat, depending your perspective), and write this blog post instead of productionizing wasmtime-dl.

Verdict

My initial goal of binding from wasm imports to dynamic libraries has been achieved (with some criminal mischief along the way). It’s not a practical end product, but I learned a lot about dynamic linking and the limits of code generation! You can check out the wasmtime-dl repo to see where I ended up, and you can pull in the crate if you want to be a victim of a compile-time crime.

This auto-binding approach obviously isn’t going to pan out for Brick. Instead I’m going to experiment with an idea I’ve only seen in Roc: the language requires an external program called a “platform” to run. The core language will remain the same, but the IO primitives and runtime characteristics will be determined by the platform. Considering the sandboxed model of wasm, this seems like a great fit for Brick! Stay tuned for a possible future post on the subject when I implement it.

Thanks to Robin Neufeld for feedback on a draft of this post.

It might seem a little odd to write

extern "C"instead ofextern "WASM". The Rust WASM team did consider a WASM-specific ABI, but ultimately decided against it. ↩︎I have no idea how this process works! I’m also not sure how much it varies by operating system. I know that all the major operating systems have their own dynamic library formats (

dllon Windows,dylibon macOS, andsoon Linux), and that the OS searches various locations for a library when loading a library. ↩︎Pun intended. ↩︎